Being an expat in Sri Lanka, I often get questions from locals about my background and how I like the country. I love to reply with “And you?”

“Where are you from? “From Russia, and you?”

“Do you like it here, in Sri Lanka?” “I do, and you?”

No one expects to be asked if they like it in their own home country. That’s what makes it fun. Yesterday a girl from my dance class asked how I like Sri Lanka and I said that by now it’s like second home. “And do you like it here?” I asked in return. “Eh…I am planning to move next year”.

She reminded me of myself at twenty two, eager to conquer the world. “Anywhere, but Russia!” was my motto. I didn’t want to “go to” as much as I wanted to “go away”. It didn’t matter where, just away from my routine, from early morning bus to work where one feels like a sardine in a jar, from -30°C in winter, from the fact that my friends were moving on with their lives, getting married, having kids (yes, being married with kids at the age of twenty two is fairly common in Russia), and I was stuck in the same place.

The view of Kremlin from Zarydiye Park in Moscow

Ok, I had a preference, I would have loved to go to Europe, like all Russians do, but Europe didn’t want me. So I ended up in Sri Lanka. What was supposed to be a six-months internship turned into one year on the island, and then another year in Brazil, and then back to Sri Lanka, and on to USA, and back to Sri Lanka (“Back to Sri Lanka” should be the name of the theme song of my life). And now it’s been eight years away from my Motherland.

When I came home to visit parents in those first years of long-term traveling, I felt… good about myself, slightly superior even to other people. “Oh no, I don’t live in Russia, I just came down for vacations, you know… I live in Sri Lanka, actually… yea, the island, beaches, palm trees, sun all year round and all that jazz…” No-one had to know that I hardly ever saw the ocean because I had to work on weekends and was getting paid $300 dollars a month. Doesn’t matter, I live abroad. Abroad is better than home, not just better — cooler.

When people asked me if I miss Russia, I replied that I miss my family and friends, not the country per se, and it was the honest, from the bottom of my heart truth. I never thought of moving back, in fact, that thought terrified me.

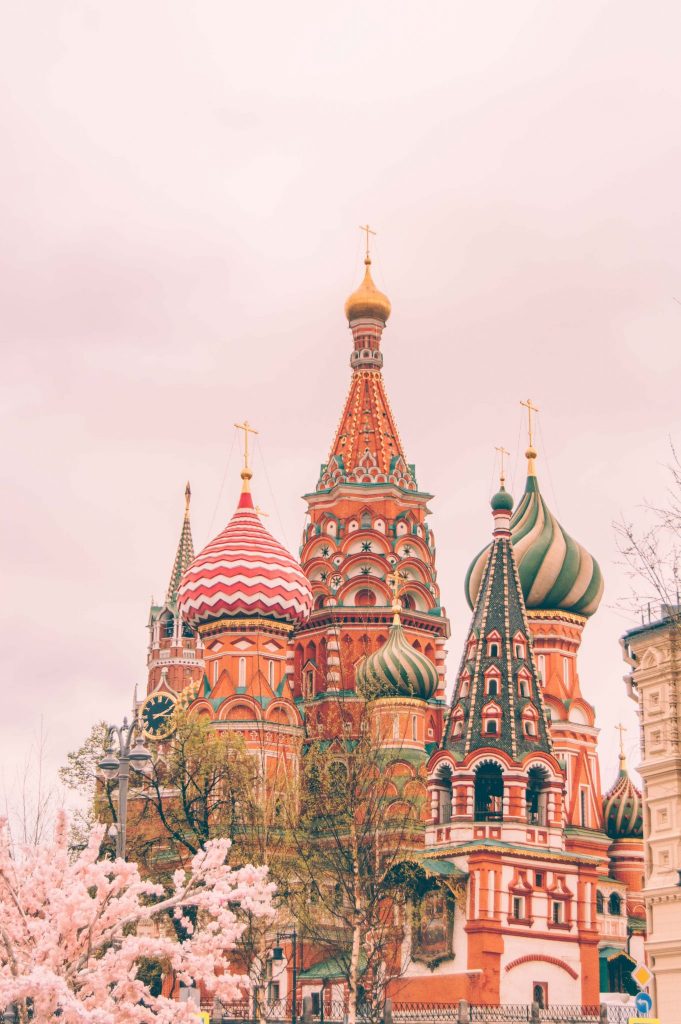

Saint Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square

After three-four years of traveling, my thinking moved from “living abroad is cool” to “living abroad is normal”. I come home once a year for a month, and this is life now. Not good, not bad, just how things are. I didn’t try to stir the conversation with my hairdresser/manicure lady/random taxi driver towards the question of where I live. I actually stopped telling unknown people all together about me living abroad, because answering the same questions became tiring.

After eight years of being an expat it hit me. I am homesick. I don’t just miss my parents, my best friends, or the taste of borsch. I miss driving in the countryside and seeing nothing but steppes and forests for hundreds of kilometers. I miss feeling in my body how vast and incomprehensibly enormous my country is. We have a word “neob’yatniy” in Russian which I loosely translate as “unhuggable” — so vast that even if you spread your arms at full length, you won’t be able to hug it. I miss that feeling.

In front of Moscow State University.

I miss sitting in the kitchen till the wee hours of the morning with my best friend, drinking tea and talking about life. I miss the freshness of a crisp winter morning and those -30°C that I ran away from. I miss eating cottage cheese with jam and sour cream every morning or at least the opportunity to be able to do it. I miss dark as the earth rye Borodinsky bread with caraway seeds, although I actually hate caraway seeds and always scrape them off.

I miss the beauty of classical Russian language with its never-ending, running like a spring, long sentences that have more punctuation marks, than words; and the whole intricate world of Russian swearing, an art form in and of itself. I miss being able to say “shall we?” while flicking my neck and expect my friends to understand we are going to drink tonight.

The feeling is more than that of missing something, the feeling is of disconnecting from my roots. The bitter realization that I don’t really know what’s happening in Russia right now and I don’t mean the political side of it. I don’t know what songs everyone’s singing at the moment, what stupid memes everyone’s quoting, what TV series everyone’s watching, what restaurants everyone’s praising, what celebrity everyone’s hating on. The little, seemingly unimportant things.

A plate of borsch and my friend’s hungry dog.

I come home to Ekaterinburg and see new buildings popping up, girls wearing sneakers (what happened to high heels even when you are taking trash out?), and take-away coffee cups —none of that existed when I left. When someone asks me how things are in Russia and what people think, I realize my answers are about eight years old.

All of a sudden, my Russianness is in question. How Russian is one if he (she) didn’t live in Russia for eight years, but only occasionally visited for a few weeks at a time? Is there a time frame when you can be still traveling and Russian, but after a certain point of no return one’s Russianness starts trickling away? And can I accumulate that lost Russianness back by taking longer vacations at dacha and eating more pickles?

A few years back I came across an article “The Problem with Where You’re “From” written by Jess of Notes of Nomads. One part of her post where she describes the way she is treated in her country of origin, Australia, after living in Japan for years, resonated with me:

“I feel a similar sense of denial whenever I visit Bendigo, the town where I was born and grew up, or Melbourne, where I attended university and began my working life. It amazes me the response I get from many people – those who feel that since I haven’t actually lived there for some years that this equates to having no right to a connection with these places. As if 24 years of my life in those cities, localities that shaped my very being and where some of most meaningful relationships occur, can and should be erased based on the grounds that I’m not up-to-date with the latest restaurant openings, or that my local accent isn’t as strong…

Then over in Japan, I have the opposite problem – you are here now but you didn’t grow up here or at least your physical appearance says otherwise. The “now” makes little difference when your ethnicity doesn’t match what is considered the “norm”. You’re not Japanese, therefore you’ll never be one of us…”

You are not here, not there. In your home country, you are not local enough because you don’t know the latest news, in your new acquired home you know all the news, but you are still not local enough, because you weren’t born there.

Being an immigrant never bothered me. I don’t mind not being seen as Sri Lankan or American, neither do I feel like a second-class citizen, as some of my friends describe it. I feel perfectly comfortable having a different skin color and a thick accent.

At Ganina Yama, a monastery not far from my hometown.

On the other hand, me being Russian and being seen as Russian is a touchy-feely topic lately which results in interpreting other people’s behaviors and words through the prism of my own insecurities.

I feel conscious discussing current affairs and the state of life in Russia with my not-so-close Russian friends because what do I know, right? I don’t live there.

A few months ago I had a heated discussion with my parents on Skype about some political BS, and when my dad said “to understand that one has to be a patriot” I interpreted it as “you don’t understand it because you are not a patriot” which made me burst into tears on the spot. I had to disconnect and make myself deliberately breath in and out for good five minutes to calm down. The crazy thing is that my dad doesn’t think I am not patriotic enough, but I guess I am afraid of it on some subconscious level?

And that is given that I do my best to stay connected. I read books in Russian, I watch Soviet classics, my wardrobe has some distinctly Russian dresses and three (!) original shawls from Pavlov-Posad, I even braid my hair!

In fact, and many immigrants will agree with me, you start following traditions of your Motherland more vigorously the further and the longer you are away from it. I mean… I make pelmeni from scratch! Something that wouldn’t occur to me if I lived in Russia and could buy a pack of pelmeni in any supermarket.

Russian Easter breakfast wth eggs, kulichi and sirniki (cottage cheese patties). Samovar is front and center.

I also made my mom bake kulichi and put samovar on the table this year, because for the first time in years I was home for Orthodox Easter. Russians don’t casually make pelmeni, bake kulichi and use samovar in everyday life. They don’t have to. They feel Russian enough. They don’t even think of feeling it, they just are. I, on the other hand, try to use every opportunity to connect.

There’s a category of immigrants who, upon moving to a new country, create their own little home in a foreign land, refuse to follow local traditions or even learn the language. Brighton Beach in New York is a good example. You enter Brighton Beach — you forget that you are in the United States altogether: everything from street signs to price tags is in Russian and that is the only language you hear around.

But although the community of Brighton Beach is distinctly Russian (or better said — Soviet), I have doubts of how much connection it has with Russia today. Brighton Beach gave me a feeling of traveling back in time to Russia of the 90s, and not even nostalgia made it feel good. Besides, I never wanted to be one of those people who don’t assimilate in their new home. On the contrary, I was always willing to be open and accepting to the language and customs of the country that allowed me to be a part of it, if only briefly.

Another borsch, prepared by my mom.

There’s a little bit of American in me with my views on feminism, racism and sustainability. There’s a Sri Lankan part too with my tolerance to spices and ants in my tea as well as an occasional unconscious head bob. There’s even a tiny bit of Brazilian with my love for dancing and three-hundred-episodes-long soap operas.

Does my heart or soul, or whatever part of me that contains my nationality, locality, connection to a country, has a limit? Is it something like a pie chart where if I carve out 5% for my Srilankanness, my Russianness should decrease by the same 5%?

I truly want to believe that my soul is more of an expanding universe than a pie chart. Wikipedia states that “the universe does not expand “into” anything and does not require space to exist “outside” it”, and Wikipedia never lies, right? If you are a physicist, please, don’t take this seriously, I love the romantic side of comparing myself to expanding universe — there’s no scientific grounds whatsoever behind this comparison. I like the idea of my soul expanding and not requiring space outside of it to contain all of my diverse localities. I want to be 150% Russian, maybe 5% American, another 10% Sri Lankan, 2% Brazilian, and I want the sum of 167% to be completely acceptable. Is it too much to ask?

Sometimes April in Russia looks like this! I am wearing my Pavlov-Posad shawl, by the way.

This long-distance relationship with my Motherland is not an easy one, long-distance relationships never are. I should know, my husband and I are from different countries. On the one hand, my love for Russia is inside me and as such can be carried with me wherever I go. It doesn’t require any physical evidence or approval of other people. On the other hand, being immersed into the routine daily life of my country whenever I travel back always makes my connection feel stronger. They say long-distance never works. It did for me, once. I have to make it work once again.

That was a beautiful piece about identity crisis when it comes to where you truly belong. I feel the same way sometimes being born an Indian and living abroad in America. I’m not sure I belong 100% in either of the places. It’s a weird push-pull of how Indian or how American I’m feeling on a regular basis. Add to the fact my husband and I are considering relocating to New Zealand. That will result in even more of an identity crisis turmoil.

Thank you for sharing, Nabeela! The push-pull feeling is a great way to describe it! While you do sometimes struggle to pin-point where exactly “you are from” and where you belong, having these diverse localities also enriches your soul and your life experience. I hope your move to New Zealand will bring only positive emotions!

Interesting article! Love the perspective

Thank you, Sam! :*

I related to what you wrote, in a way. I grew up an army brat and had no real ‘place’ I was from. Definitely I had a country, Canada, but at one point when I was 14 and faced with coming ‘home’ after 4 years in Germany – I wanted to stay.

I like the expanding Yulia vision… our hearts are elastic so expand away Yulia, expand away!

I am so glad to see that people can relate to the emotions I am feeling, and, honestly, I can’t even imagine what it’s like to move to a new place every few years as a child, must be so damn confusing! Thank you for your kind words as usual, Donnae! Expanding soul it is!

I found your site because I was googling Russian dishes I enjoyed from my childhood. Thanks for your thoughtful post. Living now in my fourth continent, the locals never perceive that I am one of them, but I’ve kept something from each place I’ve lived, and I am very thankful of that.

It’s interesting too the thought about seeking to be more “authentic” then the people left behind, I’ll definitely be making sirniki from scratch when I get back home, because I miss it.

Thanks for the post!

Hey Jonathan! Thank you for taking the time to leave a comment, this is one of my most personal posts so I appreciate when people share their experience. Where are you originally from and where are you living now?

P.S. sirniki are the best! I need to make them myself, it’s been a while 🙂

This is so purposefully written, with such passion, that I feel your words in my soul! It’s nearly prose-poetry! I came across your blog while searching for Russian recipes. I wonder if I will feel any of this when my family and I finally make our move to Russia. Although, I find being an American, particularly a white American whose family has been here for a hundred years or more, to be so rootless and modge-podged that I feel like we already have an identity crisis and we haven’t even left home yet. In fact, I feel like we need a culture, a language, a cuisine of our own to feel more rooted. Orthodoxy has provided these things here in this vast amalgamation of cultures that are no longer cultural in the present but memories of it and no longer very authentic, something we vaguely refer to as ‘American’. I miss something I never had and trying desperately to find it. Thanks to Orthodoxy, we have been provided a home in America, specifically in the Russian church. We look forward to finding home in Russia, where some of our friends have already immigrated to. When we get there, I’ll think about what you’ve written.

Hi Sara! Thank you for such a heartfelt comment, I really appreciate your openness. Where in America are you from? I know there are still a lot of Russian Orthodox churches in Alaska since it used to be part of Russian Empire. Quite amazing how people find home in the most unexpected places. I am happy you found yours. Are you planning to move to Russia any time soon?

Yulia, your post is so beautifully written, I just had to leave a comment and tell you so. And I wanted to share an experience of mine that your post reminded me of…

I’m an American, at least 4th generation on my mother’s side. I’ve never lived outside the United States, but I have lived in 4 different states that are spread apart from one another, far enough none of them share a border.

I was born in Arizona, far to the west. This almost doesn’t count, because my parents moved back to Illinois when I was six months old! We lived there until I was almost 9, when my dad got a new job and we moved to Tennessee. I lived there until half way through college (age 20), when I moved to Florida because I needed a different school to pursue my new major, and it was where my fiancé was stationed in the Navy. I’ve now lived here full time since graduating college, about 25 years, longer than anywhere else I’ve ever lived. All four of my children were born here. You’d think Florida would be home by now, but a few years ago, I found out differently…

I went through an emotionally traumatic experience a few summers ago – the details aren’t important to the story – and that same weekend, a big group of my friends were about to go up to Tennessee and spend a week on a lake in the same county I had lived in, not many miles away from my high school. They invited me to come, but I wasn’t sure I was in the right frame of mind, so I didn’t leave with them. After the first day or so of seeing them post pictures on social media, though, I completely changed my mind. I felt like I needed to escape, so I called them up and asked if I could still come. They said yes, and about 10 hours later, I was at the house.

Have you ever been really hurting, and just wanted to go “home”? That is what getting to that lake house felt like. It was quite a surprise to me, that it felt like coming home, even though I’d obviously never lived there. I’d never lived on any lake, but had spent a little time as a teenager at a friend’s house on a lake on the other side of the county. I spent a lot of time alone, and wasn’t always very social, but my friends were very understanding and just let me do what I felt like doing. I didn’t even tell my mom, who lived 15-20 minutes away from where I was staying, that I had come. For some reason, being there felt more like “home” than any place had in years.

It took me 25 years to realize that for me, “home” is Tennessee, no matter where I live or for how long.

Hi Melinda! First of all, I am sorry it took me quite a while to reply to your beautiful comment. I have been on an unscheduled break from blogging for the past 3 months. Just woke up one day and realized I am completely drained creatively and had to take some time off. So I didn’t open the blog or email or Instagram.

It makes me happy that something in my writing moved you to leave your story here. Thank you for sharing. Although I lived in the USA only for 3 years, I have to say that sometimes moving states is not unlike moving countries (I moved from New Hampshire to Texas and it was like a whole different planet). But in the end it’s not even about the differences, it’s about that feeling of home, of belonging that certain places bring you, sometimes without any logical reason. I guess the heart wants what it wants. I am glad that after so many years you realized where your true home is!

Hi Yulia! Found your blog whilst googling Russian recipes (wanted to impress my family). Going through some of your posts, I have to say, it’s very relatable. As someone who is a first generation born in the U.S. with a family who came to NY from the USSR, so much of what you wrote above resonated with me. I love Russian culture and try my very best to “stay current”. I’ve never actually been to Russia, but thanks to my family, I’ve always felt connected by way of language, eating the food, music, books, tv, etc. I still follow politics and keep up with the new music and shows but it’s hard. Just know, that keeping up with one’s homeland/culture is a choice and that already makes you a true Russian, if not more than most living there.

-A new subscriber, Nicole

Hey Nicole! Thank you for such a thoughtful comment and your support.I hope you’ll get to visit Russia at some point, it would be such an extraordinary experience for you. I myself just came home after a 1 month trip to Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Kola Peninsula where I was born. Seeing with your own eyes everything you’ve heard from parents and have seen on TV and connecting the dots would make for an amazing trip!

I love your blog so much Yulia, especially this piece. I’m a half-Russian teenage girl from France. I was born and I live in Paris, and have the most stereotypically french first and last name (Alexandra is my second name though, therefore sometimes I go by Sasha)so people assume I’m 100% French and I really hate it. I identify with your article: I constantly feel the need to express the fact that I am Russian by wearing very stereotypical clothes, eating Russian food and everything… DNA-speaking, I am just as Russian as I am French, but in reality, I don’t even speak proper Russian (I am working on it though…). My fully Russian mom has been living here since 20 years but people always ask her where she’s from due to her strong accent and foreign name and that annoys her, so she doesn’t understand this obsession I’ve always had with being perceived Russian lol. She doesnt really complain though, I know she loves it when I ask her to make piroshki or borscht 😉 Once I graduate I would love to go to Russia as a student trip to practice the language maybe. Your blog is amazing!!! Every article is like a little candy

Thank you, Sasha! Your words just made my day! It means a lot to find people all around the world who feel the same way as I do. I only hope when I have kids they feel the same way about my motherland as you do about your mother’s.

A trip to Russia sounds like an awesome idea! I am sure you’d love to experience everything you’ve heard of first-hand and practice the language. Given that Russians don’t speak much of English, your Russian will improve in no time! Thank you for taking the time to leave a comment 🙂

Wow, this hit home! I was adopted by an American and have lived in America for two years. I love America and I love the culture but like you said, I feel very out of touch with my Russian-ness. My dad does his best to try and incorporate some of my culture into our home, though, which is really nice. I’ll definitely have to ask him to help me make a Russian Easter breakfast, that picture with the kulichi and sirniki made me so hungry! There’s also this one feeling that you didn’t mention so I don’t know if you’ve felt it too, but there’s this odd sadness that I get sometimes when I romanticize something about Russia and then the reality hits me. For example, I visited with my boyfriend and we had grand plans for a romantic tour of some of Russia’s prettiest places. It was definitely gorgeous, and the trip was great, but I forgot (?) that I wouldn’t be able to hold hands or be affectionate to him in public. Where I live in America, I (a boy) can hold hands with him with nothing but a healthy nervousness, but in Russia I felt scared to do that. I might have just been my paranoia, but it was still kind of a let down. Overall though, it was fun! Also something you kind of mentioned, people don’t seem to acknowledge my Russian identity or my American one. I was only twelve when I left Russia, how could I have any memories of anything? I’ve only lived in America for two years, how could I know anything about the culture?, people ask me. It’s okay though, my close friends and my dad are cool with me being both Russian and American. I love your idea of the infinite universe thing, it really makes me happy.

P. S. I don’t know what you think about gay people, so sincere apologies if I made you uncomfortable

P. P. S. I love your blog! I don’t have any Russian friends and even though my dad is pretty educated on the culture, it’s not quite the same. I love reading your posts because it’s like talking to an old friend or something, someone that grew up with me.

Final note: I try, but my English isn’t the best haha )

Hey Nox!

First of all, sorry for the late reply! Second, you didn’t make me uncomfortable, not one bit. I also don’t think that you feeling scared to hold hands with your boyfriend in Russia is paranoid. It’s understandable. If I were you, I’d be scared too. There are some people in Russia (or shall I say “a lot of people”?) who still don’t accept same-sex relationship which is sad and I hope it will change over time.

You are an infinite universe, you can be both Russian and American. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Your English is really great, especially given the fact that you lived in USA for only two years. If you didn’t mention that English is your second language, I wouldn’t be able to tell.

Thank you for all the sweet words about my blog and for sharing your story. Blogging can sometimes feel like a one-way road: you write and write and write and sometimes there’s no reply from the readers. So when someone takes the time to leave a comment and share their emotions, it makes me really happy. So thank you!

Thank you for writing this out! You described it perfectly and surprisingly to the point. I feel exactly the same after living in US for nearly 15 years after leaving Russia in 2005. Your post made me want to go back!

Hey Lara! Thank you for the kind words! Я рада, что мои слова нашли отклик в вашей душе!

Wow. I love this. I stumbled onto your blog while looking for a stroganoff recipe I could easily pull off in Asia, but ended up going down the rabbit hole of identity and life abroad. I’ve lived almost half of my life abroad, and I’m a mutt (I’m Asian the way most Americans think they’re European). As someone who has been an outsider forever, I’m super happy I fell into your writing, though I still haven’t looked at any food related posts you may have made yet. I’ll get there, and I’ll eventually figure out stroganoff despite living in a country with the wrong mushrooms, difficult to find or expensive sour cream, and expensive beef.

Hi Mattie!

I apologize it took me forever to reply! I’ve been taking some time off blogging what with the current events directly impacting travel blogs like mine.

Thank you so much for the lovely comment! Unfortunately, I don’t have a stroganoff recipe (but that’s an idea for a future post!), but I am happy that you found something of value here anyways. It’s always nice to hear from readers who share their personal stories after reading mine. Hope you are safe and sound (and managed to find all the ingredients for the Stroganoff)!

I have only one question left. What is ‘head bob’?

I’m not satisfied with the Urban Dictionary explanation…

P.S. please keep writing, you are doing great! 100% feel the same way as you as an immigrant.

Ok, where do I even start? 😀 You have to check out a youtube video for head bob, because I can’t possibly describe it, but I can explain what it means. In Sri Lanka and some other Asian countries people use this gesture to reply to you without having to say “yes” or “no” directly. So it can mean both or something like “we’ll see”, “probably”, “let’s try”. I think I could write a whole post about the head bob and all its applications 😀